![VeryGoodCopy [Small].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5615edeae4b0b9df5c3d6e90/1560338290795-ICLESY3ZWTN79Y9312IO/VeryGoodCopy+%5BSmall%5D.png)

The rotary phone rang once, twice...

Three times. Four times.

“Aloh?”

“Yana?”

“Yes.”

“It’s Vasya.”

“Vasya?”

“Yes,” said Vasya. “Listen. Listen. Something horrible happened in Pripyat. The nuclear plant down there blew up!”

“It did what?”

“It fucking exploded! And now you’re all breathing in the radiation. You need to leave Kiev. Now! Take the kid and go East!”

Silence.

A siren went by in the distance.

“Why do we need to leave?” said Yana.

“Because,” said Vasya, “you’ll get cancer if you don’t.”

In 1986, the Chernobyl disaster happened.

To this day, it’s the worst nuclear accident in history, releasing at least 10 times more radiation than Fukushima.

The plant was in Pripyat, Ukraine, about 200 km west of Kiev, where my mom, Yana, was living with my dad and sister. I wasn’t born yet.

To “avoid inciting a panic,” the State didn’t disclose the accident to its citizens. Or to its neighboring countries. The world only learned about Chernobyl because the radiation was independently detected. Warning alarms in nuclear plants across Belarus, Germany, Switzerland and a dozen other countries lit up.

The news spread fast after that.

Vasya, my mom’s uncle, was living in New York at the time. He heard about the disaster on Nightline and called my mom. My family left home the next morning.

![VeryGoodCopy [Small].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5615edeae4b0b9df5c3d6e90/1560338954276-GAVSJCXQ67Y2JLRCZZJZ/VeryGoodCopy+%5BSmall%5D.png)

JOIN THOUSANDS OF SUBSCRIBERS

Chernobyl is now a miniseries on HBO.

It chronicles the events of that day — and the horrific aftermath.

It’s excellent. I’ve been watching it religiously.

And I’ve been listening to the accompanying NPR podcast. (Also excellent.) It features the show's creator and writer, Craig Mazin, talking at length about the creative decisions that went into making the show.

One quote from the podcast stood out to me.

Mazin was discussing a scene in which divers had to swim through a pool of irradiated water — directly beneath the core of the eviscerated reactor — to complete a critical mission.

Here’s what Mazin said about the goal of the “true” story he was telling in that scene:

“We really tried to put you in that place. Obviously some of the details we were guessing on and inventing. But the goal there is to make you feel what it must’ve felt like down there.”

This quote stood out because…

It’s an important reminder about “true” stories.

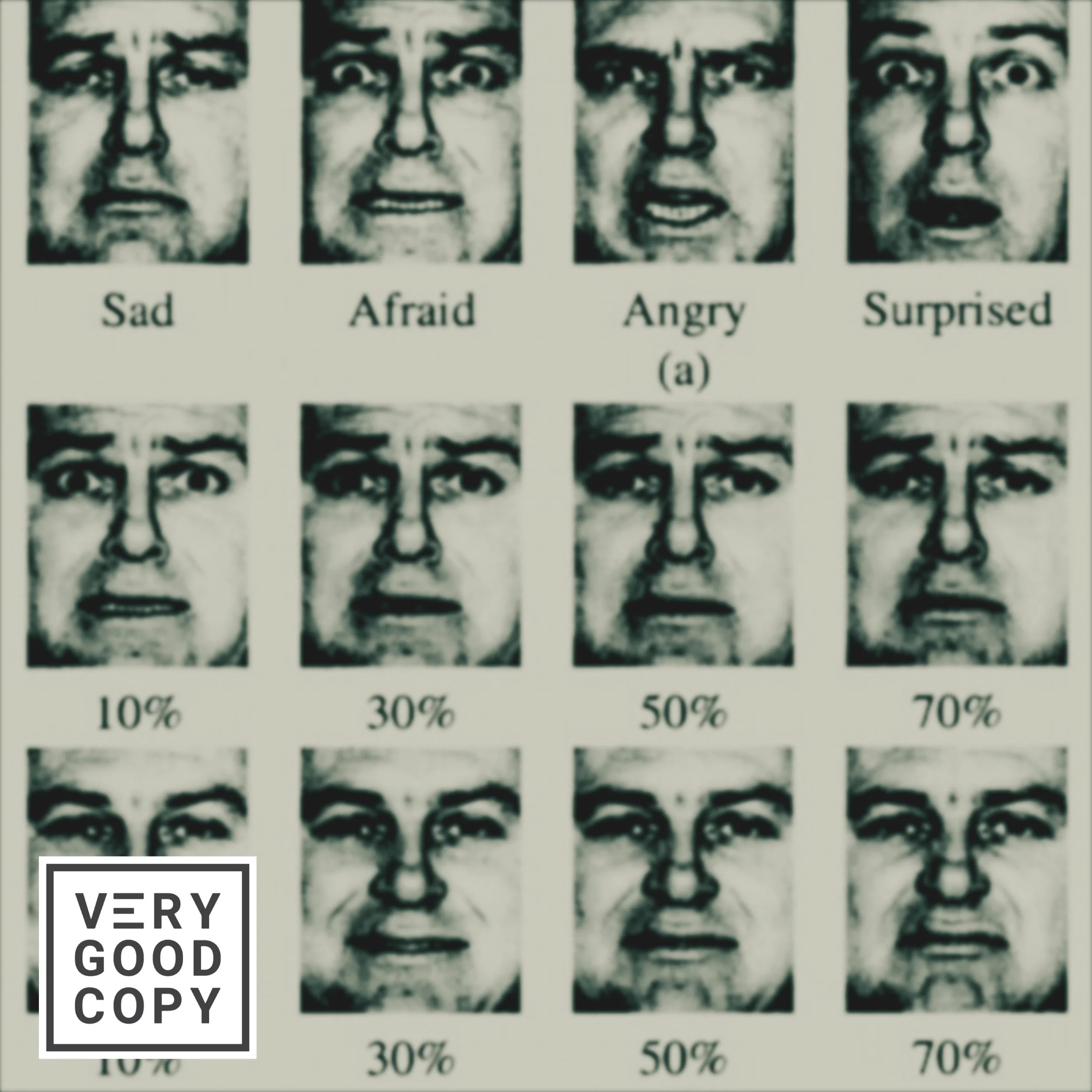

A true story, regardless of the medium, should capture the feeling of the actual event, the emotions.

A true story need not necessarily depict all of the details — the words, the chronological events — with 100% accuracy. Of course, those details are important. Of course they are. They honor real people, after all.

Problem is, when you have a limited amount of time or space to tell a story, unwavering accuracy can actually make a true story less believable and relatable, less real.

Maya Angelou once said, “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

So, to Mazin’s point, it’s alright to take creative license with a true story IF it helps the audience feel a character’s true plight, her true emotions.

For example…

I don’t know what Vasya said on the phone that day.

And neither does my mom. She doesn’t remember. His exact words are lost.

All I know is there was a phone call in the evening, and then my family left home the very next morning. Whatever Vasya said was that urgent, and that scary. And ultimately, those feelings are what matter in the retelling of the story.

This rule applies to most storytelling that demands efficiency, including movies, shows, and sometimes, advertising.

Something to consider.

LEARN TO PERSUADE

![VeryGoodCopy [Small].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5615edeae4b0b9df5c3d6e90/1560338664667-261VACKSYP3CZEN8THY5/VeryGoodCopy+%5BSmall%5D.png)

WRITE BETTER.

MARKET BETTER.

SELL MORE.

COMMENT BELOW

Judge not lest ye be judged.

![How copywriters put prospects in the buying mood [quick trick]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5615edeae4b0b9df5c3d6e90/1533095575515-C2JPAZA3C46IBX00EMM8/Put+prospects+in+the+buying+mood+%5BVGC+art%5D.JPG)